Walton-Ellis, D., Messham, L. & Tan, R. “It’s been a rollercoaster, but I wouldn’t change it”: CAT Groups in a Women’s Inpatient Service. Daisy Walton-Ellis, Leanne Messham and Ranil Tan. Reformulation 55

Abstract

This article describes the process and experience of facilitating Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) groups within a tier four inpatient service for women with a diagnosis of ‘personality disorder’. Reflections and key learning points from the groups are included. The experiences of the group members are also presented through extracts from their goodbye letters, which have been included with permission.

Background

Due to its relational focus, “CAT has particular applicability to personality disorders” (Mulder & Chanen 2013, P. 90), and has been shown to be more effective in reducing psychological distress in service-users diagnosed with ‘personality disorder’ than treatment as usual (Clarke, Thomas & James, 2013). CAT is most frequently used as an individual therapy, but adapted pilot CAT groups have also been trialled and investigated in a range of services. These include secondary care mental health services (John & Darongkamas, 2009), with female survivors of sexual abuse (Calvert, Kellett, & Hagan, 2015), and with service-users experiencing “severe long-term and complex mental health difficulties” in a secondary care service (Brummer & Partridge, 2019. p. 30). This literature provides evidence that CAT in groups can be acceptable and effective for those with similar psychological and emotional difficulties as in a tier four inpatient service, but the current research in using CAT in groups with people with a diagnosis of ‘personality disorder’ is limited.

Individuals with more complex presentations can be excluded from such interventions e.g. when assessing “readiness” for therapy (McMurran, 2012). There is also a lack of consensus on how to best adapt the CAT model for use in a group context with this population. Therefore, two CAT groups were run in a specialist inpatient service as a pilot; the structure of the groups and the learning and reflections from the facilitators are discussed below.

CAT Groups: Structure & content

Protocol and content

Two CAT groups were run over a two-year period and were led by two facilitators: a consultant clinical psychologist and a trainee clinical psychologist, with an assistant psychologist co-facilitating when either were unable to attend. The first group ran for 24 sessions and the second for 20, with sessions lasting 75 minutes each. The group sessions followed the three stages used in individual CAT therapy: reformulation, recognition and revision.

Participants

In total, seven of 11 women completed the groups across two cohorts. The average age was 29.4 years old (range 20 - 36 years old). In the first cohort, two women who were offered the group chose not to take part, as they did not believe a therapy group would suit their needs. Four women completed the group, and one dropped out at session 13 of 24. The average number of sessions attended was 18 of 24. In the second cohort, three women completed the group and one dropped out at session 9 of 20. The average number of sessions attended was 15 of 20. The two women who dropped out of the groups were provided with follow-up sessions. External factors impacting on their capacity to utilise the group were cited as reasons for withdrawing from the group.

In general, sessions were missed due to planned appointments (e.g. a hospital visit), sickness or levels of distress that meant the women did not feel safe to attend. On these occasions a ‘check-in’ was facilitated to support the women to keep connected to the group, reflect on key themes from missed sessions and to understand non-attendance in relation to the group reformulation. Group members missed more sessions towards the beginning of groups. This may have reflected anxiety and avoidance associated with the group process, however attending to this as described seemed to hold the group, and all the women in both cohorts were present for the final session.

The majority of group members had several previous hospital admissions and a long history of involvement with mental health services. Multiple and significant experiences of interpersonal trauma are prevalent amongst this service user population, and group members experienced difficulties related to their experiences of trauma. This included self-harm, interpersonal difficulties, low mood, voice hearing, flashbacks and disassociation.

Reformulation

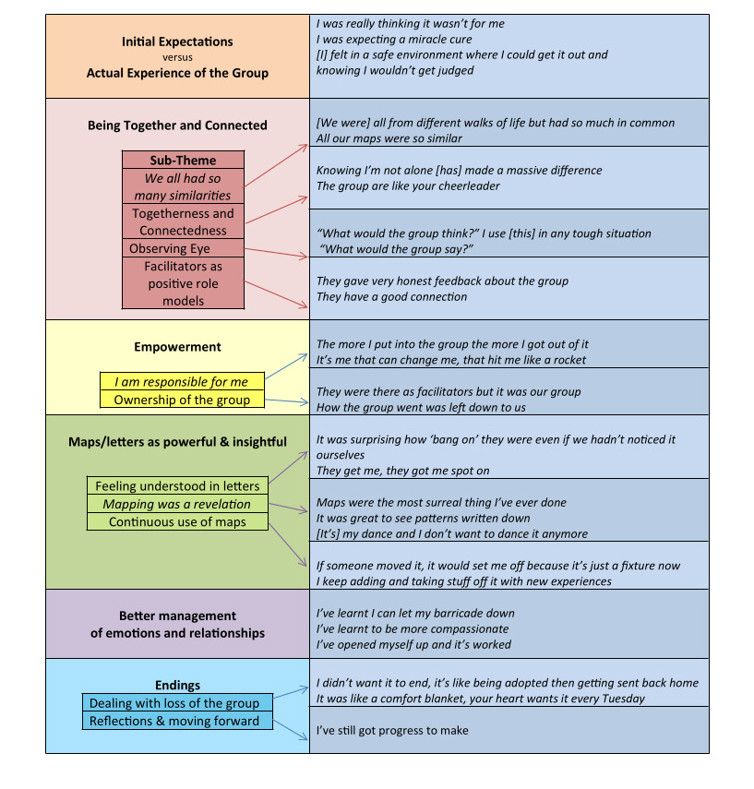

The facilitators met with each group member before the start of the group to develop a relationally defined goal, which they agreed could be shared with the other members of the group (e.g. “To understand why I push others away. I want to feel more comfortable in relationships with others”).

Each group member also completed the Goal Attainment Scale (Turner-Stokes, 2009) before and after completing the group in order to track the impact of the group on individual goals. The majority of women (6 of 7) reported that the group had helped them to achieve their self-determined goal, and three women rated their chosen problem as ‘much better’.

Individual goals were initially written onto flip chart paper and attached to the wall during the group sessions. Key points from the group discussions were then added. During both groups, group members seemed to describe similar procedural sequences related to their individual goal.

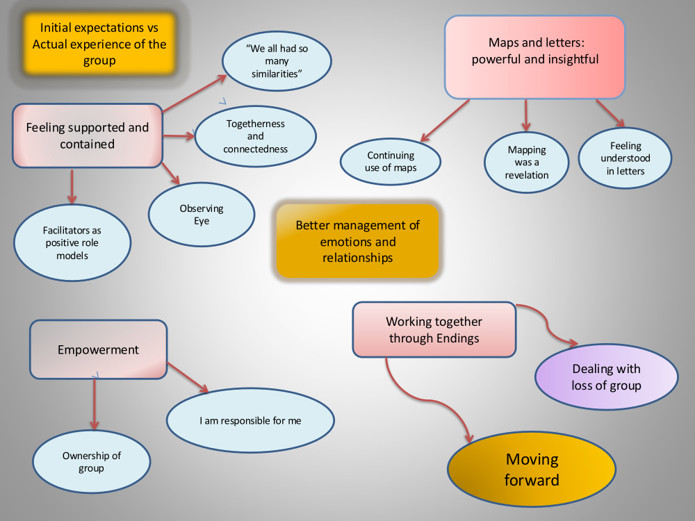

This allowed for the development of a shared map or sequential diagrammatic reformulation (SDR) as opposed to individual maps for group members. The map was also informed by the conversations and observed dynamics during sessions. A group reformulation letter was shared at session five.

Recognition

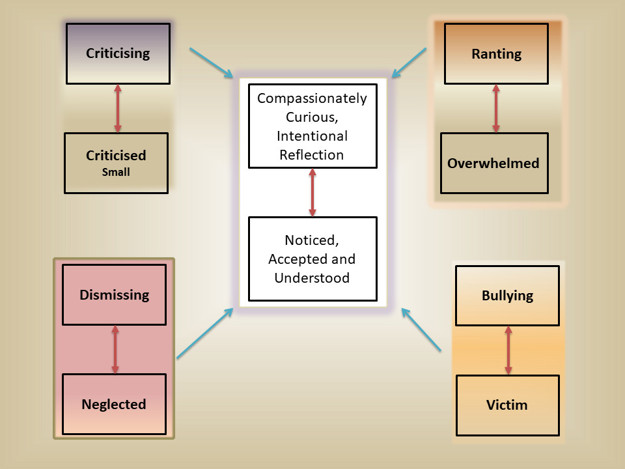

The map or SDR reciprocal roles and procedures were printed out onto separate pieces of paper. Each session began with group members and facilitators working together to construct the map on the floor, so that it could be actively used to anchor discussion (see Figure 1). Every group member had a counter (such as an image or word from a magazine that they chose which represented them) and were asked to place this on the map or SDR to symbolise where they felt they had been on the map that day or week. The group then discussed and reflected on this together, in order to facilitate the process of recognition and reflection.

Revision

During group discussions, the facilitators aimed to role model and encourage members to respond to each-other’s and themselves with validation and compassion (an exit in itself), and to generate broader ideas about exits the group members could use. In some instances, the facilitators highlighted exits that group members had already taken but not been conscious of. As exits were discussed they were added onto the SDR. A diverse range of exits were identified, but they could be broadly clustered into four themes: expressing emotions, tolerating emotions, seeking social support and using self-compassion.

Key Learning Points

1. Building safety (containing – safe)

Understandably, the group context could feel overwhelming and unsafe at times, given group members’ experience of trauma and adversity. The first sessions were spent developing shared group agreements which included how women could keep themselves safe, such as agreeing a safe word which could be used to ‘pause’ the group. The group members also brought in self-soothing and grounding items such as smelling salts; they used these and encouraged others to use theirs when they noticed others were starting to feel overwhelmed or ungrounded.

Building a sense of safety for group members also included the after-session support provided by the nursing staff on the ward. For example, staff would ‘check-in’ with members following the group if needed. It was helpful for staff to be willing and able to stay with the women’s distressing feelings in the short-term to support them to move towards their therapeutic goals (rather than, for example, always relying on PRN medication). The facilitators supported the staff team’s understanding and engagement in this by debriefing the team after each group session and discussing the group at the women’s multi-disciplinary team meeting, so there was a shared understanding of the process and learning from the group amongst the wider team.

2. Pacing (repetition/structure/slow pacing - recognition/ containment)

In order to keep the group safe and to work within the women’s zone of proximal development (ZPD), it was clear that the pace of the group within sessions had to be led by the members. It was easy for sessions to feel too challenging for group members, as well as for the facilitators, therefore they started slow, involved lots of repetition and the facilitators held the same structure each week. This was particularly important when the topic or disclosures within the group were very emotive, when the group session had a more explorative nature, and in the initial stages of developing the map before considering exits.

3. Creativity and dialogue – connecting with others

Within each session, using creative exercises was a useful way of facilitating dialogue and moving between cognitive and feelings-based moments. One exercise that was particularly significant was the six-part story (Dent-Brown, 2011), in which people were asked to draw a story in six parts about a character who overcomes a problem or achieves a goal. This allowed women to use art and dialogue to share something about themselves, in a way that provided a narrative and context to distress and adversity. Another example was the use of worksheets depicting a series of simple line drawings to represent different types of relationships.

The facilitators used these as a basis to ask questions about the images such as the group-members’ relationship to the images and aspects that ‘stood out’ to each woman. This helped individuals to indirectly think about the types of dynamics that were important and potentially problematic for them.

A ‘human scale’ was also used, where members of the group placed themselves on a continuum to represent how much they agreed or disagreed with different statements and discussed how their experiences fitted with others’. This started with neutral items (e.g., “I enjoy walking”) to items which had a more relational/ emotion-based focus (“I respect myself”). This encouraged dialogue between group members, such as noticing similarities and differences, which helped normalise and validate their experiences. Overall, these exercises helped to identify relevant reciprocal roles and associated procedures. It supported group members to share parts of themselves and to reflect on aspects of their internal and relational world which they may have struggled to do so easily, without such scaffolding.

4. Physical exercises and grounding (coming back to the body – grounded and present)

The core dilemma faced by group members (in both groups) was to either avoid and disconnect from emotions; or become completely overwhelmed by strong emotions and to manage these in potentially unhelpful or unsafe ways. By its very nature, the group was emotive, and so each session became an opportunity to identify, explore, make sense of, validate and contain extreme emotional states.

Grounding strategies and modelling were used to support group members to find a helpful balance between the two extreme states of ‘avoid or explode’. This included increasing their capacity to become present and tolerate difficult emotions in a contained way, as well as to express or ‘discharge’ emotions in a way that felt safe. These exercises often had a physical nature to them, which was helpful in regulating emotions and gaining connection with the body/self-soothing. This was particularly important at the end of each group session, to facilitate moving away from difficult emotions in a mindful and skilled way, distinct from unplanned, unmentalised avoidance. Physical exercises aimed to support group members to get back into their bodies in order to enable them to go on with the rest of their day. Exercises included using ice packs, throwing and catching games and copying each-others physical movements.

5. Holding on (holding on together – hopeful/encouraged/ resilient)

At times, the group could feel incredibly overwhelming and uncertain. Women could be in extremely vulnerable places; struggling to keep hope and manage their safety. The facilitators too could feel overwhelmed by the emotional intensity of the group. Reflecting on this, there was a pull towards an ‘avoidant’ procedure shown on the SDR. For example, facilitators questioned whether they should keep running the group or whether they should use a more structured approach to ‘turn down’ the emotional intensity.

This intensity was however, a felt experience of the women’s reality. It felt imperative to stay anchored and contained (through the use of reflection and supervision outside of the group) in order to hold the feelings elicited within the group. It was key to use the strategies described above to keep the group safe but ‘moving’. The women in one group talked about “holding on...hour by hour, minute by minute”. This became an exit for both the facilitators and women; a need to hold the relational frame in order for the group to work through the turbulence together.

6. Ending together (attending to the end – anchored/achievement/in control)

As per individual CAT, the facilitators discussed the ending of the group from the first session. There was an anxiety about the ending and a pull for women (and facilitators) to avoid the ending in some way (e.g. finishing sessions early). “Staying together and ending together” helped to anchor the group and keep the focus. The SDR helped women make sense of their feelings about the end, and there was an incredibly powerful shared sense of achievement about getting to the end and reflecting on the journey. The end of the group was marked by a goodbye letter from facilitators, which was read out in the penultimate session. Group members were also encouraged to write a letter - these letters showed a genuineness and reflective capacity that was extremely moving to listen to on a personal level. With permission, some extracts are included below.

“I’ve learnt that I am not as different to others as I thought I was, I’ve learnt that I am more connected than I thought. This is big for me, a milestone, because for most of my life I have felt that I wasn’t human, that I was too separate from everyone else.”

“I have learnt things about myself that I think will help me in my future. I now know that I can have difficult times but deal with them better by using the exits rather than going to the extreme of hurting myself etc. I do think that I have more to learn but the skills I have learnt in the group can be built upon and help me to cope better.”

“My greatest achievement has definitely been to go into the group therapy sessions where I had to open up about things I wouldn’t normally would. If I was to struggle I would go back to the work we have done in cat group, would look at the map to remind myself that there is a way out.”

“It has also made me realise that other people have had some of the same experiences that I have and people aren’t that much different and everyone has the same emotions…I have surprised myself for being able to speak about personal things in a group when I couldn’t even speak to staff. It has helped me understand that people won’t always use what I tell them to hurt me.”

Conclusions

It is hoped this article shows it is feasible to deliver CAT groups in inpatient settings, with service-users experiencing trauma related interpersonal difficulties which may have previously excluded them from therapy groups. Facilitating CAT groups can be emotionally demanding but extremely rewarding. As with individual therapy, the CAT frame can help navigate the inevitable ‘pulls’ to enact aspects of the group dynamic which are problematic, cut-off or harmful. This is a small sample and further work would benefit from comparing outcomes across several groups. Moreover, it would be helpful to explore further what CAT groups might offer ‘over and above’ individual therapy. Overall though, consistent with previous work, CAT groups appear to provide opportunities for normalisation, validation, connection and peer-to-peer dialogue and learning which go beyond what is possible in individual CAT, giving powerful opportunities for relational change.

Correspondence:

daisy.walton@slam.nhs.uk

References

Brummer, L., & Partridge, O. (2019). Effectiveness of Group Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) for Severe Mental Illness. Reformulation, Summer, 29-31.

Calvert, R., Kellett, S., & Hagan, T. (2015). Group cognitive analytic therapy for female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 391-413.

Clarke, S., Thomas, P., & James, K. (2013). Cognitive analytic therapy for personality disorder: randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(2), 129-134.

Dent-Brown, K. (2011). Six-Part Storymaking–a tool for CAT practitioners. Reformulation, Summer, 34-36.

John, C., & Darongkamas, J. (2009). Reflections on our experience of running a brief 10 week cognitive analytic group. Reformulation, Summer, 15-19.

Kerr, I. B., & Ryle, A. (2006). Cognitive analytic therapy. In S. Block (Ed.) An introduction to the psychotherapies (4th ed.) (pp 267-286). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

McMurran, M. (2012). Readiness to engage in treatments for personality disorder. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 11(4), 289 – 298.

Mulder, R., & Chanen, A. M. (2013). Effectiveness of cognitive analytic therapy for personality disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(2), 89-90.

Turner-Stokes, L. (2009). Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: a practical guide. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23(4), 362-370.