Stephen White and Jason Hepple, 2020. Eight Session Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) Improving Access to Psychological Therapy (IAPT) service – description of a model and method. Reformulation, Summer, pp.16-20.

Key Points

This paper gives an illustrated clinical description of an eight session CAT model developed for use within an IAPT service endorsed by the ACAT training committee.

The early mapping of relational patterns is emphasised without a formal narrative reformulation letter.

A brief narrative reformulation is included in the goodbye letter.

An eight session CAT model may be suitable for wider use in IAPT services in the UK.

Introduction

Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) as described by Dr Anthony Ryle has typically been practised as a sixteen session individual modality with one follow-up appointment at three months (Ryle and Kerr, 2002, Ryle et al, 2014). For more complex clients, however, twenty-four sessions with three or more follow-ups has been widely applied and researched (Ryle & Golynkina, 2000, Clark et al, 2013). Eight session CAT, however, has always been an acknowledged briefer form and it is usual for trainees to have a mix of eight, sixteen and twenty-four session cases in their training log. Eight session CAT has been positively evaluated within IAPT services for anxiety and depression (Kellett et al, 2018), and a two site evaluation comparing CAT to CBT, which included data from Somerset, has been presented and is being prepared for publication (Kellett et al, 2019).

Since 2013, eight session CAT within IAPT primary care services to complement Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and other psychological treatments for clients with anxiety and depression. has been adopted. CAT has been used preferentially for clients screened as having more complex relational problems, personality disorder traits or histories of adverse childhood experience. The adoption of the eight session model has been pragmatic so that CAT offers a comparable length of treatment to other non-CBT therapies within IAPT, taking into account the pressures on the service due to the volume of referrals. This use of CAT has been supported by the inclusion of CAT as a listed psychological therapy for IAPT Serious Mental Illness – Personality Disorder, at University College London (UCL-CORE).

A CAT therapy is traditionally centred around three relational tools. The reformulation letter is an empathic re-telling of the client’s story read out to the client, typically, in the fourth of sixteen sessions, where links are made between past ‘survival strategies’ or procedures and current relational target problems. The sequential diagrammatic reformulation or ‘map’ is the main work of the middle phase of therapy where client and therapist work together to visually depict these procedures and their exits in often a series of evolving maps. As therapy progresses reformulation moves to recognition of current obstacles to progress and the revision of dysfunctional procedures and the joint discovery of exits. At the end of therapy there is the exchange of goodbye letters between the therapist and client. There is reflection on the journey of therapy, the enactment of procedures in and outside of the therapy relationship and a summary of exits and things to take forward into the future.

Kellett et al (2018) suggest that eight session CAT in IAPT is at least as effective without the use of an early reformulation letter. The eight session model has also evolved without this early tool; this is pragmatic. IAPT therapists see a high volume of clients and gathering enough information in perhaps two sessions and then spending time outside of the therapy writing this into a reformulation letter proved difficult to sustain or supervise adequately. It was decided to concentrate on the more flexible early mapping of procedures with the emphasis on the early building of an active collaborative therapeutic alliance, with a shift of the narrative form of CAT to the goodbye letter. It is noteworthy that a similar move has been made in the application of CAT tools to an open CAT group (Hepple & Bowdrey, 2015).

Brief description of a method for eight session CAT in IAPT services

Sessions one to three

The emphasis of the first three sessions is on the building of a collaborative therapeutic relationship and the gathering of information relating to the client’s previous experience. In the first session there are various administrative tasks related to the situation of the service within IAPT. These include completing the consent form, recording GP details, risk documentation and key contacts, medication documentation and an introduction to the outcome measures to be collected.

The client is then introduced to the relational nature of the CAT model. The therapist is explicit that the therapy relationship itself is based on a collaboration; a joint curiosity around relational patterns that have emerged in the past as ‘survival strategies’ but that are now counterproductive (dysfunctional procedures). The style of working is described to the client as ‘doing with’ rather that purely educational or ‘doing to’. It is made clear to the client that disclosure of painful material relating to the past can proceed at the client’s own pace and it is important for the client and therapist to work in the ‘zone of proximal development’ – a CAT concept borrowed from the work of the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1978) that describes the productive zone of developing insight and progression existing between the particular client and therapist.

Time is then spent gathering information that will inform the later CAT formulations. CAT has the concept of ‘target problems’. This is an explicit way of acknowledging the limitations of a time limited therapy and drawing attention to the need to focus the therapy on what the client brings to the table. Target problems attempt to start with the client’s categories of understanding rather that being limited to symptoms or formal diagnoses. Identified problems can be as diverse as ‘my anger’, ‘my drinking’, ‘other people always let me down’, ‘I feel like a failure’, ‘my depression’ or ‘I feel lost’. Once agreed upon the therapist then tries to uncover the past relational experiences that can be mapped later into procedures in the form of CAT’s traps, dilemmas and snags. It is also important to ask about the client’s aspirations, hopes and dreams for the future. Where would the client like to be in two years time? What are the obstacles to reaching that? At some time in this initial phase it is good to draw out a genogram and identify the key early relationships with care-givers and with peers in childhood and adolescence.

Below are a series of questions that CAT therapists are introduced to in order to help them gather this early stage information:

Early formulation by the therapist

The therapist, on reflection and in supervision, begins to formulate tentative procedures around the agreed target problems. This process is based on both the patterns elicited from the client’s history but also from the therapist’s direct experience of working with the client. The enactment of procedures in the therapy relationship can give very useful insights into relational patterns that are repeated in outside experience. For example, a client may appear anxious to please the therapist and be worried about ‘getting it right’. Who was this originally in relation to? What response is the client expecting if they ‘get it wrong’? (This could, for example, be fear of attack, blame, criticism or being ignored and dismissed). The therapist may take the opportunity to not enact this expectation by reassuring the client by not taking the attacking / critical / dismissing position that is anticipated by the client.

The therapist then begins to formulate procedures relating to the target problems brought by the client. In CAT these take three forms: Traps are essentially negative feedback loops (an avoidance trap, for example), dilemmas appear when survival strategies take polarised alternatives (for example, perfect control or perfect mess), while snags are more profound forms of self-sabotage of success or happiness (I can have nothing for myself as I feel underserving, for example). The CAT tool the ‘Psychotherapy File’ lists many examples of these procedures an can be used in this initial stage of therapy either as homework or in the session.

Session four

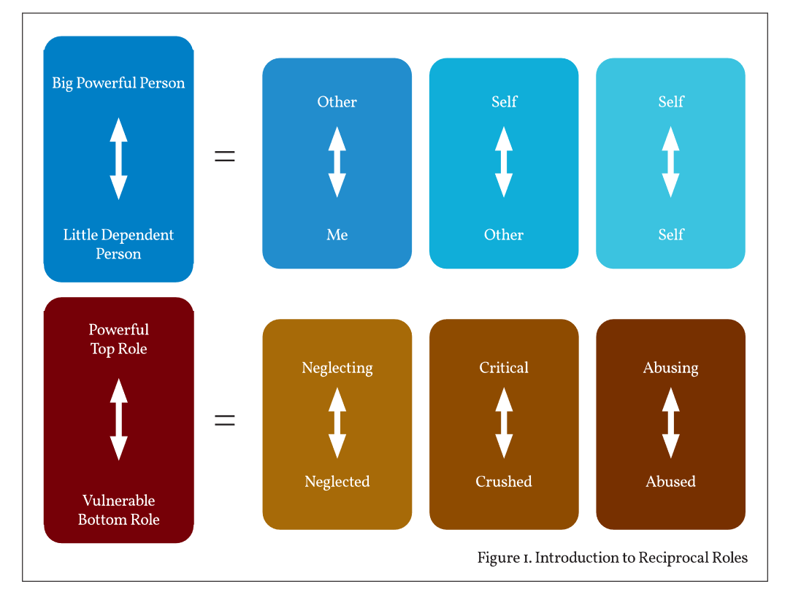

In typically the fourth session the client is introduced to the central CAT concept of reciprocal roles using the explanatory diagram shown in Fig. 1.

Reciprocal roles represent relational patterns that have an explicit cause and effect embedded in them. In the explanatory diagram the ‘top role’ position is identified as a ‘big powerful person’ while the ‘bottom role’ is identified as a ‘little dependent person’ – the client as a child. This explanation has been found to be easy to convey to clients and quickly taps in to the hurt frightened child roles and makes links to their relational causation. A therapist might say, for example: ‘So if your father often came home drunk and was aggressive to your mother, where would that have left you as a child in that situation?’ The client may identify feelings of fear, anxiety, placation or anger and wish to protect or to take revenge. The next stage of the diagram shows how what were initially self to other reciprocal roles can be internalized into self to self patterns of relating.

Many forms of self-harm can be conceptualized, for example, as an internalized abusing to abused reciprocal role where, for want of the power to rescue or take revenge, the client / child turns the angry feelings against the self in the form of self-cutting or suicidal actions. Another example could be a client who was dismissed and neglected as a child and later turns this neglect against the self in the form of self-neglect; maybe not washing or looking after their home or health. Finally, an experience of a critical and judging ‘big person’ can lead to a striving response that can then be internalized into self-criticism and perfectionism leading to the inability to sustain tasks or cope with failure or setbacks.

The example reciprocal roles given in the explanatory diagram can be the starting point for dialogue about the client’s own experience; both in the past and in the present (including in the therapy relationship). This can lead on in the same session to the therapist beginning to map the client’s core reciprocal roles and the way that are interconnected by procedures that perpetuate the client’s target problems. This early mapping can, if the therapist is confident, be improvised in the room with the client or may be partially prepared in supervision and presented tentatively to the client as a starting point.

Sessions five to seven

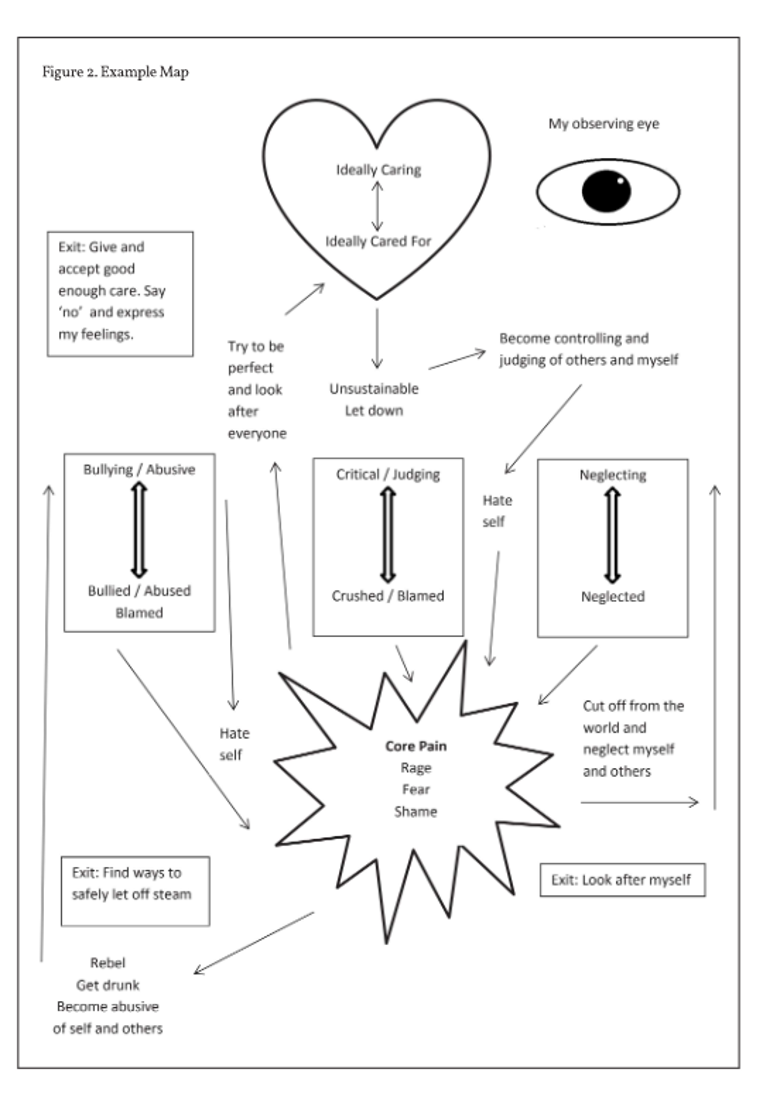

These sessions work towards the completion of a map that incorporates the core reciprocal roles identified and the way they link to the client’s target problems and the procedures that link the roles together. There is explicit description of the dysfunctional nature of these procedures; ‘survival strategies’ that are understandable but no longer helpful. The concept of ‘core pain’ may also be added to the map to name the unmanageable feelings derived from the hurt child bottom roles that have been identified. Different colours, chosen by the client, can be used to aid recognition of the different reciprocal role self-states, for example, ‘hot’ colours may be linked to aggressive or critical states whereas ‘cold’ colours may represent neglect and abandonment.

This is the recognition phase of the therapy, where the client develops growing insight into the roots of their procedures but is then able to identify ’re-enactments’ of these procedures in events that happen in the time between sessions and sometimes in the sessions themselves. The CAT concept of the ‘observing eye’ recognises this growing ability to take a ‘meta-position’ or ‘helicopter view’ of the patterns that have been so harmful over the years. This is an internalisation of the reflective ability of the client-therapist dyad as an ability for self-reflection.

If there has been a strong re-enactment of the client’s reciprocal roles in the therapy relationship, then this is an opportunity to prevent therapeutic rupture, seek repair of the therapy relationship and to move to a position of joint reflection on ‘what happened between us’. Reflection on the weekly outcome measures may help identify re-enactments as they emerge. It may be important for the reciprocal role that was being enacted between the client and therapist to be present on the map so that both can see it from an observing position. Examples of common re-enactments are: A striving client in response to a perceived critical / dismissive therapist then becoming critical and dismissive of the therapist and the work done, or perhaps a neglected / abandoned client, fearing the end of the sessions, seeking to disappear from the therapy before it is over and abandoning the therapist first. These patterns can be brought into the therapy dialogue and learned from.

As the end of the therapy approaches ‘exits’ are added to the map as recognition of patterns turns in to the ability to revise and make different choices in to the future. It may be particularly important in an eight session therapy for the therapist to name the approaching ending in every session and to allow the client to reflect on how they might feel once the therapy is over and what procedures they may turn to in order to avoid the feelings the end evokes. In session seven the client can be invited to bring a goodbye letter to the therapist for the final session.

Fig.2 is an example map that links the core reciprocal role states with the core pain of the client that is derived from the hurt child bottom roles. Procedures link the core pain with compensatory powerful or idealised positions that turn against the self and lead back to the core pain. A representation of the observing eye and three exits are also shown.

Session eight

In the final session there is an invited exchange of goodbye letters. The task for the therapist here is to put into brief narrative form the main links between the client’s early relational patterns and the target problems and procedures that have been worked on in the course of the therapy. There is also reflection on the therapy journey, re-enactments in the therapy relationship and naming of the jointly discovered exits and ability for self-reflection. The therapist typically goes first and the client is then invited to read any prepared letter following this. If the client has been unable to write a letter, sometimes it is good to find time in the session to allow the client to try to put something down, maybe while the therapist is tidying up the final map or sorting out the final outcome measures. There is not usually a follow-up session with this eight session model.

Appendix 2 offers an example of a fictional exchange of Goodbye Letters that relate to the map in Fig.2.

Closing thoughts

CAT was always designed to fill the need for a time-limited, focussed therapy that is affordable in the public sector in the UK. This eight session model is adapted to the demands of a high volume primary care IAPT service and inevitably has to cut some corners in order to allow an element of reformulation, recognition and revision within the eight sessions. An advantage of working in primary care is that many clients have not been ‘institutionalised’ by long periods in secondary care services and can be quick and motivated to make links and changes to their procedures. That is not to say that eight session CAT will be enough for everyone. It may be that in future services positioned between primary and secondary care, eight, twelve or sixteen session CAT may be available. Also, the model of serial therapy with breaks between interventions that allow for the delayed effect of recognition, may be suitable for some clients by combining CAT guided self-help, individual CAT and later group CAT modalities.

References

Clarke, S., Thomas, P., & James, K. (2013). Cognitive analytic therapy for personality disorder: Randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 202, 129–134. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp. 112.108670

Hepple, J., & Bowdrey, S. (2015). Cognitive Analytic Therapy in an open dialogic group – adaptations and advantages. Reformulation, 43,16-19.

Kellett, S., Stockton, C., Marshall, H. et al (2018). Efficacy of narrative reformulation during Cognitive Analytic Therapy for depression: Randomized dismantling trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 239, 37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.070

Kellett, S., et al (2019). The effectiveness of CAT compared to CBT - when delivered in England’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Programme. Presentation at ICATA international conference, Ferrara, Italy, June 2019.

Ryle, A., & Golynkina, K. (2000). Effectiveness of time-limited cognitive analytic therapy of borderline personality disorder: Factors associated with outcome. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 73, 197–210. doi:10.1348/000711200160426

Ryle, A., & Kerr, I. B. (2002). Introducing Cognitive Analytic Therapy - principles and practice. Chichester, UK: Jon Wiley & Sons.

Ryle, A., Kellett, S., Hepple, J., & Calvert, R. (2014). Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) at Thirty. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 20, 258-268. doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.113.011817

Vygotsky, L., S. (1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. ambridge, M.A: Harvard University Press.

Correspondence:

jason.hepple@sompar.nhs.uk

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Steve Kellett and Liz Fawkes.

Appendix 1

Below are a series of questions that CAT therapists are introduced to in order to help them gather this early stage information:

Typical early questions:

‘What brings you here? What can I help you with?’

‘How long have you been troubled by these feelings/thoughts?’

‘What would you hope to achieve from our working together?’

‘How would you best describe yourself as a person?

‘Perhaps we could start by you telling me a bit about your early life. Let’s imagine you have just arrived in the world. Who was around – mum, dad, siblings, grandparents?’

‘Can you give me three words off the top of your head to describe your mum, dad, other important figures?’

‘What are your memories of your early life at home, how were things between your parents, your siblings etc.?’

‘How did this make you feel?’

‘How was your experience of schooldays, teachers, friends etc.?’

‘How did you cope with difficulties then?

‘As you moved on to your teenage years did you have any significant friendships, relationships? How do you remember these? How was lifeat home at this time?’

Appendix 2

Example of a fictional exchange of goodbye letters that relate to the map in Fig.2.

[Therapist’s Goodbye Letter to Client]

Dear Julie,

Now that we have reached the end of our CAT therapy I have written to you, as I said, to reflect on the journey we have been on. When we first met you told me that your target problems were that you ‘feel exhausted all the time’ and that ‘I hurt people’. You seemed very low at that time and also seemed worried about me being able to share your problems. In some ways you seemed to be looking after me for fear that you would hurt me too. We were able to see that these patterns started in your childhood. You told me that your mother was always very critical and blaming of you; that you were supposed to look after your younger sisters while your mother went out partying. You took on the role of a ‘parental child’ but this was too much responsibility for any child of your age and left you feeling exhausted and neglected. Sometimes you would run away from the world and hide in a neighbour’s shed rather than going to school.

You told me that things got worse when your mother’s boyfriend sexually abused you when he was supposed to be babysitting. You wonder whether your mother knew but chose not to rock the boat as she wanted to live her own life. It was very sad when you told me how lonely, hurt and ashamed you felt at that time. As you grew older you began to rebel – fuelled by the anger you have about what happened to you. You went out to pubs and clubs with ‘a bad crowd’ and now feel ashamed for some of the things you got up to. Another part of you tries to make up for these doubts about yourself by taking on to much for others; trying to be the perfect mother and wife. Ultimately you feel taken advantage of and that no one cares about you. This can make you retreat into your bed and be ‘ill’ or secretly drink to numb how you are feeling. Eventually, demands build up on you and you feel bad that you have hurt and neglected those close to you.

As we began to understand these patterns we were able to add the ‘observing eye’ to your map. Maybe it is now possible to see these patterns beginning again and make some different choices? We have already found three exits. The first is to allow yourself and others to be ‘good enough’ and that you can say ‘no’ when you are exhausted by explaining honestly how you feel. You now have daily ‘catch-ups’ with your husband what have improved things between you. The second exit is to do with looking after yourself instead of retreating or going back to drinking. The yoga class you have started is a great example of this and you have met some nice people. Thirdly, when frustration builds up when things don’t go well it may be good to find safe ways to let off steam. You have thought about getting involved in the football again; this seems a good idea and again gives you chance to express how you are feeling to friends.

Julie, once you began to trust that I could look after you in our therapy you really took on board the work we were doing and even drew your own map, which is now on your fridge! I am hopeful that the exits we have found can lead you in a different direction and heal the relationships you have with those closest to you. It is been a pleasure working with you and I wish you all the best for the future.

Andy

[Client’s Goodbye Letter to Therapist]

Dear Andy,

I can’t believe the time has gone by so quickly! It was only a few weeks ago when I rocked up in a mess – exhausted and hating myself. I had never really connected what I was doing with the things that happened to me as a kid. It all seemed normal to me and I just thought that I was rubbish and weak. I can now see what I am doing – at least most of the time. It is amazing that I can say ‘no’ and people can listen to me saying this if I explain rather than just going off the rails. Things are a lot better at home.

I am sad that we are ending today but I really think I can remember to speak to people and look after myself a bit better. I don’t know how you cope with so many people’s problems to deal with, but thanks for listening to mine and thank you for all your help.

Julie